The RL Q+A:

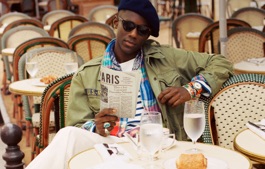

Jacob Gallagher

The Wall Street Journal Men’s Fashion Editor on his new coffee-table book with Phaidon

Any student of men’s fashion, or any subscriber to the Wall Street Journal, has likely come across Jacob Gallagher’s work. His twice-weekly column for the newspaper, where he is the Men’s Fashion Editor of the paper’s “Off Duty” section, smartly covers the beat of shopping, style, and the endless swell of trends in the wide world of menswear.

While his reporting covers a wide spectrum of style considerations—“I might talk to readers who are just out of high school who are into the crochet-clothing trend one week, and folks that are older and trying to figure out more traditional style pathways another,” he says—his sharp eye for and deep knowledge of menswear has recently taken on an even bigger scope.

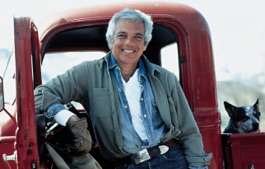

The Men’s Fashion Book, recently released from Phaidon, compiles 500 brands, designers, and fashion figures into a handsome coffee-table compendium, introduced and coauthored by Gallagher. A spiritual successor to the publisher’s iconic The Fashion Book, which is tailored toward womenswear, the new book seeks to give menswear its due in a similar format, from Beau Brummell to Ralph Lauren and many, many more.

When you’re considering the entirety of the men’s fashion space, how do you decide what’s included in that 500?

At one point we were actually up to almost 800. We were really trying to assemble a range where, whether you read the whole book or just flipped through, you would get a good sense of the key players within men’s fashion.

There are definitely some people and brands in there that haven’t been in the mainstream conversation, and people that we wanted to have reconsidered. And, then there are the people that you would expect, like Ralph Lauren, or Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons and James Jebbia of Supreme. But, we also wanted to look at menswear from a different perspective in some points; primarily, not being so Western-focused. There are some brilliant African designers in there, South American designers, Mexican designers. There’s, of course, a huge group of designers from Asia. I hope that we can turn the reader on to at least some names that they might not have been familiar with, prior to picking up the book.

For the book’s Ralph Lauren entry alone, you had to distill 50 years of history, a host of brands, countless iconic designs, a whole world of creativity—all of that into a couple of paragraphs. Then, you had to do it 499 more times. How do you even start a project like that?

It’s hard. You want to give everyone their due, and make sure the reader is going to understand both how this person or brand emerged, and why they matter. Those are the two things I had in mind, particularly the latter.

With someone like Ralph, there’s no mistaking why he matters. But, you also want to put it into very plain language, so that the reader gets it very quickly. Something I really hope for with the book—whether it’s with someone like Ralph, who’s so integral to menswear that it’s almost like he’s part and parcel with it, or it’s someone like Bill Kaiserman, who young readers might not be as familiar with—is that in both cases, it leads people to dig up more for themselves. I think one of the great things about Ralph Lauren, and other fashion legends, is that they’ve had long careers. And, one of the great ways people interact with fashion now is going back and rediscovering different parts of their work over those years.

It’s interesting to see how all these historical threads are interwoven. I don’t often stop to think about my wardrobe in an overarching historical and cultural context. Reading the book almost forces you to do that, in a very absorbing way.

We wanted to make that direct. Within each entry, there’s a notation at the bottom for other relevant designers and figures, so if you’re looking at one designer and you see a name down there, you can flip the page and go look at that and start to piece together the broader conversations. We don’t have an entry for “prep” or an entry for “streetwear,” but you can make those connections yourself by moving back and forth through the entries we do have—and then you’ll see, oh, Ralph also was in conversation during this or that time. You can see those connections.

I think it’s particularly nice because we talk a lot on an individual level, but the way people dress right now, it’s very rare that someone is wearing all of one designer. So, it’s nice to pull out those connection points because that feels very close to how people actually dress today—and how those combinations become a person’s individual wardrobe.

One thing I appreciate about your writing in the Journal is that it feels a bit anthropological, looking at trends through the lens of a broader cultural idea. Did that approach segue well into the book?

As my dad always says, there’s nothing new under the sun. And, one thing I’ve always enjoyed about menswear writing is that everything does make “sense.” You can track everything and see the order of how trends bubble up, and how they get adopted, and how they go away. The book was different in the sense that you’re studying that clear story of how designers bubble up—but you also see how that story is aligned with the culture and trends of that moment, and how that designer might ride that to incredible heights, or midground heights, or they might not even be appreciated in their time.

Your book shows how wide the range of menswear is, and your articles cover so many fast-moving trends. How can someone find their own personal style amid both those things?

It’s taken years to arrive at where I wanted to be with my wardrobe. But, one great thing about being in this moment is that there are very few rules—you don’t have to dress to fit in. You can be into fashion on its own terms, you can feel your way through and find out what works for you. I think we underestimate how widely held a cultural standard the idea of having to dress like your boss, or to “dress to impress,” was. That doesn’t necessarily exist anymore. And, I think people should take that freedom to find out what works for them, their lives, and what they feel comfortable in—what makes them feel the most themselves.

- Courtesy of Phaidon

- Courtesy of Jacob Gallagher

- Courtesy of Bruce Weber