Speed Painters

The greatest of Grand Prix posters achieve the unimaginable feat of freezing a race car in motion. Through the decades, few artists have done it better than these, and though prices for their work are on the rise, it’s still a buyer’s marketMotorsports are defined by motion: the blur of a high-powered automobile whooshing by, fans jumping to their feet and cheering, a checkered flag fluttering in the distance.

And yet the art form that most fully captures the early days of Grand Prix car racing is still—a sketch that freezes a moment in time; an image that somehow conjures motion while deploying none. That art form is what once was the lowly advertising poster: illustrations made to promote motorsports events and printed in limited number, especially those signed by two names in particular—Robert Falcucci and Géo Ham. Their names might not be well known outside collecting circles, but the best examples of their work have been steadily rising in appreciation and price. Both have appeared in auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. In 2020, a 1938 poster of an Automobile Club de France event run at Reims by Ham sold for $11,500, far exceeding its expected price and earning first place at Sotheby’s Original Racing Posters sale. That same year, another Grand Prix poster—for the first Swiss Grand Prix, held in 1934, and created by the artist Ernst Graf, a relative unknown whose non-poster work bore little resemblance to the futurism featured in racing posters—sold for $18,000 at Swann Galleries, despite some minor tears and folds.

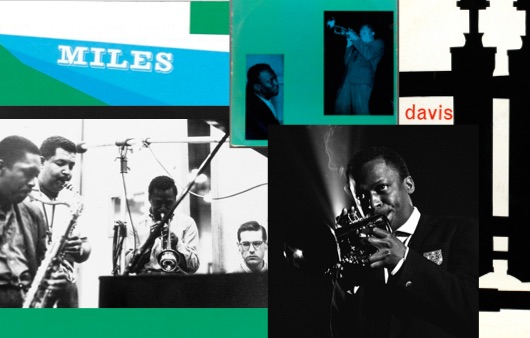

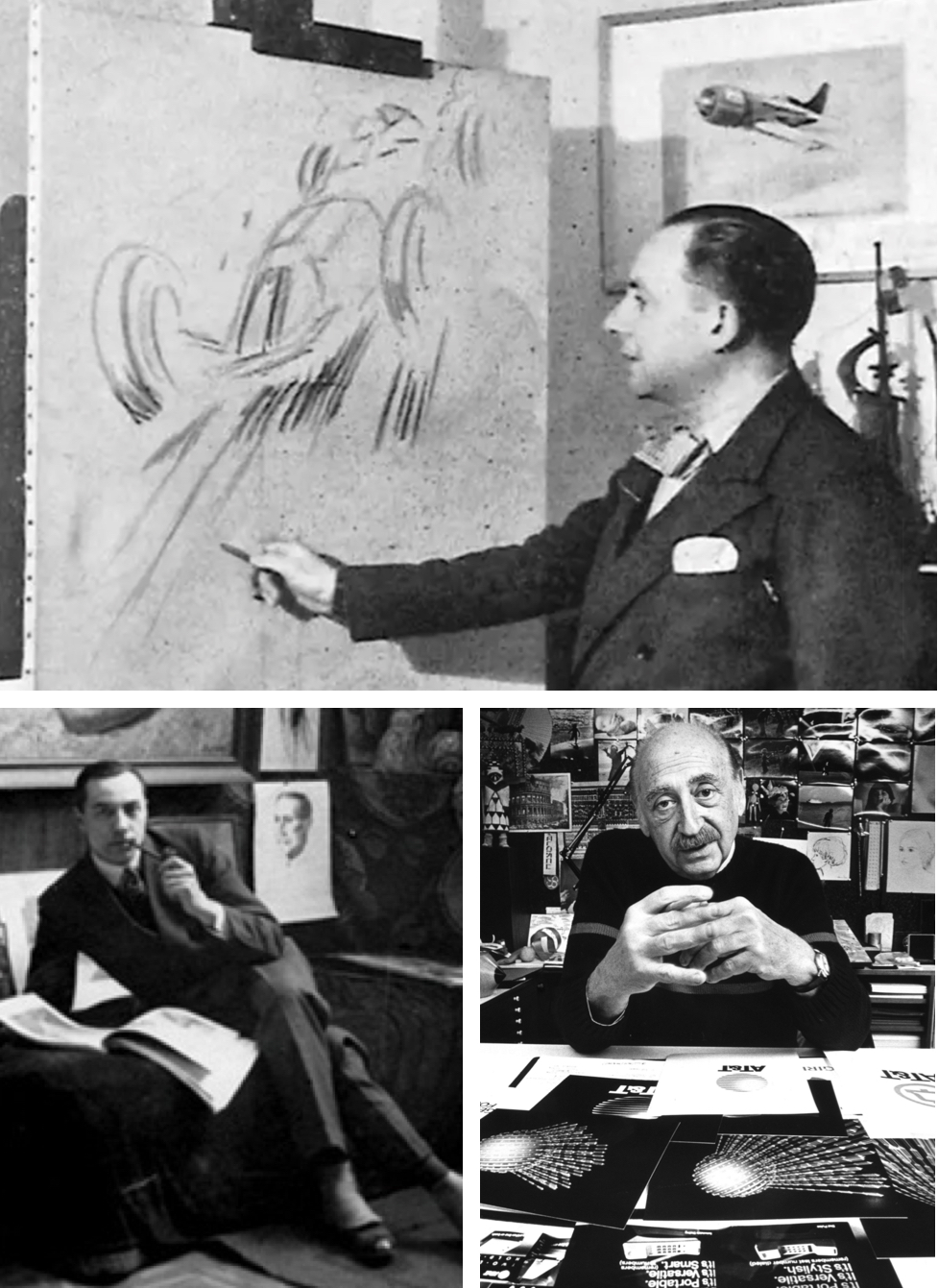

Clockwise from top: George Hamel, who signed his works Géo Ham; Saul Bass, the graphic designer, famous for his film-title sequences, including those for the early Bond films; and Roberto Falcucci, who created a robustly expressive Art Deco style.

Of course, as with anything collected by an enthusiastic crowd of obsessives, there is an X factor. With Grand Prix posters, it is, like most great works of art, the product of scarcity—those from the Art Deco period between 1930 and 1950 are especially rare. And then there’s the allure of the racing scene itself, one associated with style, privilege, adventure, and exotic locales. (Not for nothing do some of the Grand Prix posters portray such markers of the good life as yachts, sailboats, and grand estates.) Affixing such a trophy to your wall evokes the thrill of the successfully completed chase—and connotes the seductive power of discerning taste.

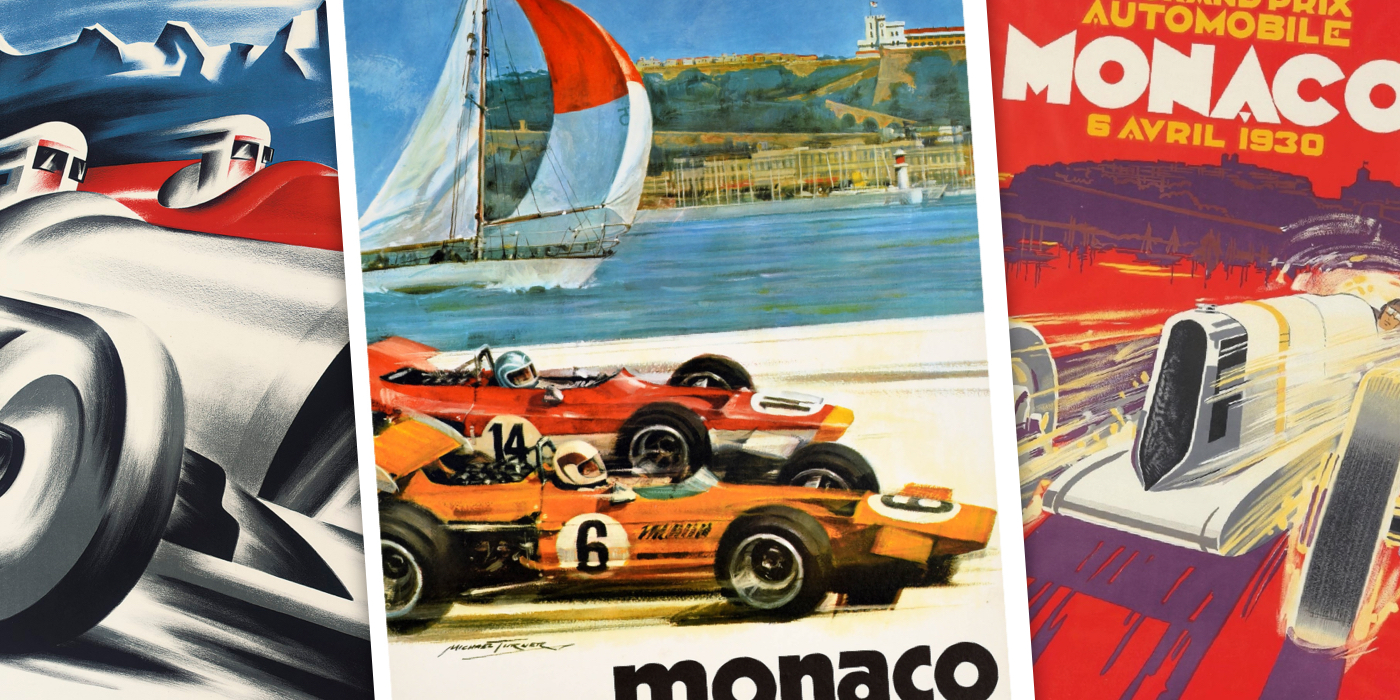

The rise in interest and value of this rarefied form of memorabilia goes hand in hand with the sport itself. On April 14, 1929, Monaco hosted the seventh Grand Prix event in history, and it quickly became the most popular race on the circuit. The next year, French illustrator Robert Falcucci, who studied at the École des Arts Décoratifs and had created ads for Renault, began producing posters for the event—creating a robustly expressive Art Deco style that is still associated with the genre today. Nicolette Tomkinson, of Tomkinson Churcher, a London-based art consultancy specializing in vintage posters, cites Falcucci’s third Monaco poster as especially noteworthy for its “action-packed” scene. “In a masterful display of pastels, he contrasted the tranquil and sunny slopes of the Riviera with the blur of two speeding racers,” she says. The excitement, the danger—the cars fly along the steep edge of the Mediterranean below—practically swerves off the paper.

From left: Ham depicts the battle between an Auto Union GL and an Alfa Romeo; Bass chooses abstraction over Art Deco for the movie poster of Grand Prix; Falcucci captures a duel between day and night.

Art Deco era posters courtesy of Tomkinson Churcher.

In 1933, the Monaco Grand Prix turned to Georges Hamel, better known for his iconic signature Géo Ham, and now considered the most talented automobile poster artist of his era. His work is recognizable for a distinct visual signature: a driver’s scarf waving in the wind, a subtle way of suggesting motion in a static image. Hamel, another Frenchman who was also a graduate of the École des Arts Décoratifs and a veteran creator of images for both the auto and aviation industries, made ingenious use of Monaco’s palm trees. The six posters he created for the Monaco race between 1933 and 1948 are considered the most beautiful—and the rarest.

Those he painted in 1935 and 1936 are particularly coveted by collectors. The first depicts the “Silver Arrow,” a Mercedes W25 that owes its nickname to its raw metal exterior—the car’s original white paint, as the story goes, was supposedly stripped off so the car would hit the required weight limit. (Note the Alfa Romeo trailing it up the hill, which foreshadowed the actual results.)

The second captures the battle between a German Auto Union GL—the first of the rear-engine race cars—and a brilliant red Alfa Romeo through a tight turn, against a backdrop of yachts and cruise ships. A more idyllic scene of action combined with setting would be hard to conjure. (As an aside, a forerunner to the Alfa—the 1931 Monza 8C 2300, which won a Grand Prix in 1932—is now parked in Ralph Lauren’s garage.)

Later Grand Prix poster artists continued to work in the style pioneered by these forebears. The poster for the 1963 Monaco Grand Prix by French artist (and Renault car designer) Michel Beligond reads like an homage to Falcucci’s 1930 poster, with a foregrounded red racer silhouetted by a blue car in pursuit, the sea on the right side, and a cityscape on the left. (A nod to mid-20th-century sponsorship requirements appears in his work for the 1966 Grand Prix de France: a pack of cigarettes.) In 1970, Michael Turner painted a stunning scene with two cars neck and neck, with a background sailboat seemingly competing alongside them.

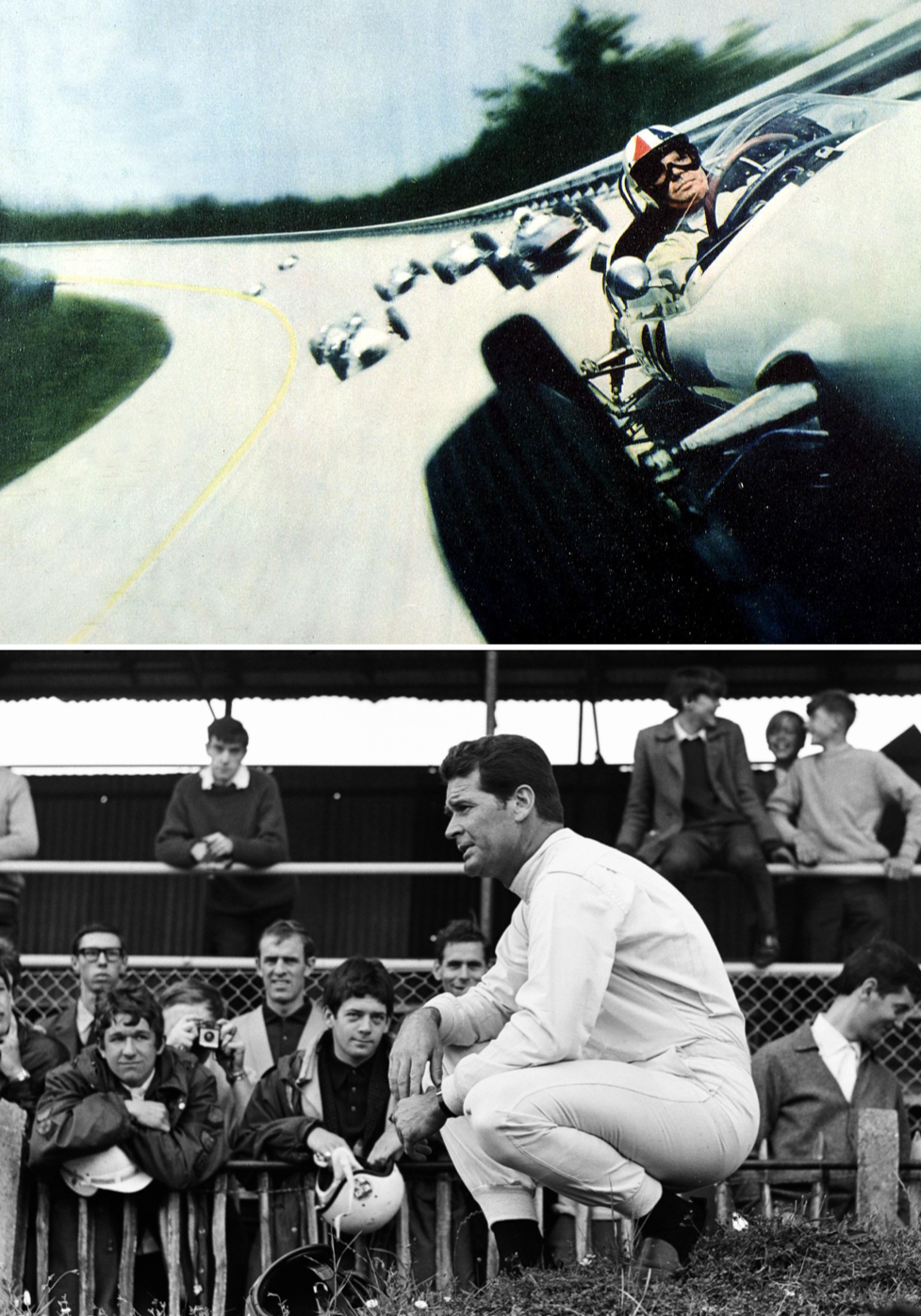

This anxiety of influence even held true when it came time to create the poster for the 1966 movie Grand Prix, starring James Garner with Japanese icon Toshiro Mifune in a supporting role. The art, by the legendary Saul Bass (of James Bond title credits fame), carefully mimics the movement and style of those posters, with a blurred race car playing a starring role. It also fetches a nifty price—Bass’s personal copy is on hold for more than $7,500 on 1stDibs.

By the ’80s, however, the posters, in an effort to be modern, grew spare and repetitive. Placing Marlboro’s well-known logo prominently in the composition clearly became a priority. Meanwhile, the earlier artwork began to become prized quarry for a particular type of racing aficionado. By the late ’70s, the likes of Paul Newman and the renowned driver René Dreyfus were regulars at the Auto Art Exhibition, an annual exhibition held in Lakeville, Connecticut, where posters were sold alongside racing-inspired sculptures, photographs, and other types of rare memorabilia. Then the doubters were more plentiful. “Automotive art is not yet completely accepted as a field of artistic endeavor,” one of the show’s organizers acknowledged to The New York Times in 1979, and then convincingly refuted it. “You don’t have to be a car nut to appreciate this show. All you have to do is to like fine art.” The growing acceptance of this assessment is, of course, one reason these works are likely to continue to increase in value.

The race poster tradition is also very much still alive, and that’s yet another aspect that creates such interest in the overall history of the genre, especially in the works which can make a claim to be more than mere illustrations. Take one look at the recent work commissioned for F1 races in Miami and Austin, and you’ll quickly see the difference between a Falcucci or Ham and these retro imitations which aren’t meant to be more than souvenirs of attendance.

Scenes from the film Grand Prix, starring James Garner, Toshiro Mifune, and Françoise Hardy, among others. It won three Oscars in 1966.

Michael Turner pits a sail boat against two drivers and gives the scene a vibe of suave ’70s saturation.

For those who may be interested in collecting, a few words of advice: To begin, look beyond Sotheby’s and Christie’s. The Scottish auction house Lyon & Turnbull—working with Tomkinson Churcher—will offer a selection of Le Mans posters in an upcoming sale on October 25. (Not Grand Prix, to be sure, but Grand Prix–adjacent, with prices expected to be attractive, somewhere around $1,000.) There is also Poster Auctions International from Rennert’s Gallery, a New York–based auction house devoted to vintage posters. At the time of this writing, you could find a Géo Ham of the second Paris Grand Prix—more a jolt of color than of action—for $1,700. As with any treasure hunt, poster fortune favors the bold—and a quick—click of the mouse. It is likely already gone.

Those simply wanting to learn more can try to get their hands on Grand Prix Automobile de Monaco Posters: The Complete Collection, a 2010 book written by the noted collector William W. Crouse. The tome is no longer in print, but it can be had for nearly $1,600 from a third-party seller on Amazon as of this writing.

Of note for those with long-term dedication is what happened to the collection of Jacques Grelley, a native of France and former race car driver who witnessed D-Day as a child and ultimately settled in Arlington, Texas, as a wine distributor. Dubbed “The Prince of Posters,” by Autoweek, he amassed the largest collection of racing posters in the world—roughly 3,200, with an emphasis on early Grand Prix works—before he passed away in 2014 at age 78. He left no survivors but had been selling memorabilia through a now-dormant online business, Racing Posters. His collection was sold to several collectors by l'art et l'automobile, in both private sales and at auction. The collector might be gone, but the work lives on—and you can visit a trove of posters at the auction house’s gallery/barn at its ranch in Harper, Texas.

MORE FROM THE POLO GAZETTE

Tough & Refined

The art–and eternal now–of putting two surprisingly unexpected things together roars to life in this fall’s Polo Originals collection, inspired by the golden era of Grand Prix car racing

By Jay Fielden