The RL Q+A:

Pride 2022

Four voices from our campaign weigh in on the impact, history, and legacy of the Pride movement

ARIEL NICHOLSON

Fashion model and advocate

On the personal journey that led to being the first trans model on the cover of Vogue…

I had a lot of support when I was younger from my family, being trans. I went to a support group at an organization called the Gender and Family Project, which supports trans kids and their families. When I was a tween, I was in a documentary for PBS which spawned a story for Vogue. They reached out to the head of the organization and asked if he knew of any trans kids and their parents who’d be interested in doing a story and my mom and I were interviewed for the magazine. She’s my number one supporter and I wouldn’t be who I am or where I am today without her. Once the story and photo shoot came out, that sort of spawned my whole modeling career.

I definitely envisioned that for myself. Being a girl is obviously who I am, but also playing dress-up has been a huge part of my identity from such a young age. And it was a way for me to self-actualize and express myself to the world and to others. I’ve always had a passion for dressing up and performing. I definitely had modeling on my mind, but it wasn’t until I had a growth spurt after I started going on estrogen—and I just went straight up—that I really started to consider it.

I think about what the outcome would’ve been if my mom wasn’t supportive, if she wasn’t there for me from the beginning, if she hadn’t done her research and been open and loving and available. I’ve been able to live authentically as who I am and been able to live an amazing life because of her support and because of her advocacy. And when I see that trans kids are being denied that, and they don’t have access to the mental health and community resources that I had growing up, it’s very concerning for me.

It’s one of the most rewarding experiences of my life to see young children just know unequivocally who they are and being able to express that. And that was something that was true to me as well. I was able to express myself from a very young age. These kids know what they’re doing. They know who they are, and they need that support. Acceptance is what’s going to protect them. Openness is what’s going to protect trans youth. My trans siblings inspire me to embrace my true identity. And by that, I mean all trans people in my community. I consider them all my siblings, because I think that we’re all going through really similar experiences, and that solidarity and support is something that I will cherish and hold with me for the rest of my life.

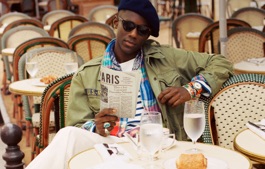

KEITH BOYKIN

Author, journalist, and cofounder of the National Black Justice Coalition

On the importance and legacy of the Stonewall riots and the meaning of Pride today…

The Stonewall riots were the event that took place in 1969 that really triggered the LGBTQ movement, the modern movement. And it happened here in New York City at the Stonewall Bar in Sheridan Square in Greenwich Village, where a group of police officers tried to raid the bar, and the bar patrons responded by retaliating. They refused to leave at first, and then once they were forced out, they attacked the police because the police had been targeting them because they were queer. And so the people who were there were furious about it, and it continued for days. And it wasn’t just sort of the stereotypical image that we think of in terms of the gay movement. They were a real diverse mixture of people, black and brown and white people. When we talk about our movement, it’s important to see representation. And that means that we are a diverse movement. We have a diverse community—we have all different types of people and all different stripes and sizes and colors and backgrounds and shades.

Today, the challenges are rooted in the movement’s success. There’s been so much success in the past decade or so in the LGBTQ struggle that some people have started to feel that there isn’t any more work to do. And other people have started to feel threatened and to create backlash against it.

Pride has so many different meanings today. I don’t think there is one way to celebrate Pride and I don’t think it means the same thing for everybody. For me, for example, I love New York Pride. I live in Los Angeles now, but I always come back to New York City for Pride. I've been to Prides all over the country—LA, San Francisco, D.C., Atlanta—but [New York] is the most diverse experience of any Pride I’ve been to. It’s a combination of different people from different backgrounds who are all coming together at one of the biggest events in the city. It’s a fascinating way for people to celebrate themselves, to celebrate their identity. We don’t all have to be the same. That’s important. The diversity doesn’t mean that we all have to fit into some sort of cookie-cutter mold. It means that we get to be ourselves. You get to be you, and I get to be me, and we can all be fabulous together because of that.

STACEYANN CHIN

Poet, performer, and activist

On art as activism…

I want the ordinary parts of me to be present and I think making art makes room for that, because then I can still talk about Prop 8 when we needed it and I can still talk about whether the monarchy has any power or right to be in Jamaica. I can talk about these ways in which books are being banned.

Art becomes a physical bridge that people can walk across. A young queer woman living in, say, one of the townships in Soweto in South Africa, might not be able to come to New York, but [she] can go on the internet and watch a young woman who’s not unlike [her], whose body is not like [hers], whose politics are different, whose everyday life is different, and they can write a poem about falling in love and not being accepted by family and that can connect [her] to that person and help [her] to feel less alone. That can become a way in which humans can say, I am not alone. Even if I feel alone, even if these walls are all I have to envelop me and call and give me some love and a hug, if my whole family doesn’t love me, someone else can write a poem, someone else can sing a song, someone else can create a play, that reminds me that I’m not alone. Not only am I not alone, but there’s a way through this difficulty.

I ran away from Jamaica when I was 24 because I was attacked by a mob of boys when I came out as a young lesbian. Somebody can read my book, read poems that I’ve written, read plays that I’ve written and say, “My God, this girl was physically attacked by 24 boys and really hurt and here she is at 50 able to fall in love and dance somewhere in Barcelona with a lover and have a child who’s 10 years old.”

Philip Picardi

Journalist, divinity school student, and advocate

On curating an oral history of fashion’s response to the AIDS epidemic for Vogue…

There was an exhibit that was about fashion through the decades that Valerie Steele curated at the museum at FIT. At the time, I was a college kid who was obsessed with fashion, and I was going through this exhibit to learn more about the history of the industry. And I get through the ’70s, so we’re seeing sequins, we’re seeing Studio 54. Then I get to the ’80s—it’s more sequins, it’s big shoulders, it’s all of this exciting, kind of cartoonish approach to fashion. And then I get to the ’90s and the room was stark white and it felt like I was entering a funeral. And I didn’t know what happened. I went to Catholic school, my whole life. I had parents who were really uncomfortable with having a gay son.

And I remember one of the first things my godmother said to me when I came out of the closet was, “I just hope you don’t get sick.” And I thought she was talking about the common cold. I was like, what does that have to do with me coming out of the closet? Little did I know she was talking about HIV/AIDS. And so I was entering this room, this white room of the museum. And what I didn’t realize was that this room was filled with the ghosts of my history, a history that had never been taught to me, a history that I had to then work really hard to locate, to understand from an intersectional perspective.

And so every time, as I was coming up in the industry, that I came across an older gay man or someone who had lived through this experience, I would take the time to chat with people. I would try and talk about this period of time. And every time I asked someone about it, I learned a new name. I learned about the famous makeup artist Way Bandy. I learned about the incredible Black gay designer Patrick Kelly, who was the first American designer to show in Paris. I learned about, of course, Williwear, Willi Smith, another incredible Black gay designer, about Fabrice Simon. The list goes on and on. The list is sadly quite endless. So I was really lucky to talk to some of the industry’s luminaries—Mark Jacobs, Michael Kors, of course Ralph Lauren, Bevy Smith, Beth Ann Hardison, [and] a whole host of people whom I’ve admired for my whole life. And I was touched by the ways that the community eventually came together.

I was more touched by the little stories of people who tended to others’ deathbeds, who called the parents of men who didn’t know their sons were gay. I was really moved by just the way that this epidemic had animated the heart and soul of a community, of a fashion community, that was a community before it was an industry. And I guess above all, I was struck by the fact that people still wanted to party. Simon Doonan said it best. He was like, there was this horrible scourge and yet everyone was at their creative peak. It was like with death so omnipresent, so imminent, queer people buckled down and were the most brilliant they’ve ever been. And that is literally a testament to the queer spirit. It is a testament to what we have to offer this world. And it is a gift we keep giving to this world.

And sometimes it feels like the world spits it back in our face, but we turn that spit into glitter every single time, you know? And so cataloguing that story, talking to everyone, dealing with the manuscript, which I have to say my friend Dan Levy, who created Schitt’s Creek, helped me to actually whittle down into a cohesive episodic kind of storyline, which I really appreciated because he’s such a magnificent storyteller. And then of course, the wonderful team at Vogue who published it and made a beautiful experience of it. It was one of the highlights of my career.

- © Ralph Lauren Corporation